When I started constructing the vast fantasy worlds and histories of the Phantammeron 25 years ago, I had come across the problem of naming schemes and languages used in my books. I found it might be helpful to create a so-called ‘fairy tongue’.

With so many place names and characters I was quickly overwhelmed with a hodgepodge of words and names in my books with almost no basis for their origin linguistically. Trust me when I say I’m no Tolkien! Unlike Tolkien I knew I would never have the interest, scholarship, skill, patience, or passion needed to construct artificial languages for the many races of beings in my fantasy books. And yet I knew had to build something lasting and true to support the vast array of place names and characters used in the books.

That’s when I started researching the idea behind such a project at the local library and how I might make fantasy language-building work for me.

Because my books were mythopoeia and not traditional epic fantasy, part of the mythology required the depth of a real fantasy language with real historical and spiritual meaning behind it. That’s when I remembered my years as a teenager starting in 1980 playing Dungeons and Dragons and the concept of the “Common Tongue”, a simple language said to be shared by all creatures in those role-playing worlds. The idea would be to first create a common framework all my languages could derive from.

In my case that quickly became the starting point for what I call the Fairy Tongue of the Phantammeron, the dominant language used by the Fey and many other races in the fantasy books. I then came up with a very simple concept to build such a language so that the end result was as rich and meaningful as Tolkien’s Sindarin or Quenya. Yet mine would have far less of the complexity of his languages. Besides, I wasn’t building a true Fairy language, just the illusion of one. I was simply needing a system to generate place names and words when needed. I could never embrace a comprehensive lexicon as Tolkien had done. For such constructs in my case, I felt, must serve the narrative and the story only, not the other way around.

And yet, strangely, something unseen and beautiful would come of my exploration into fantasy languages for the Phantammeron novels…

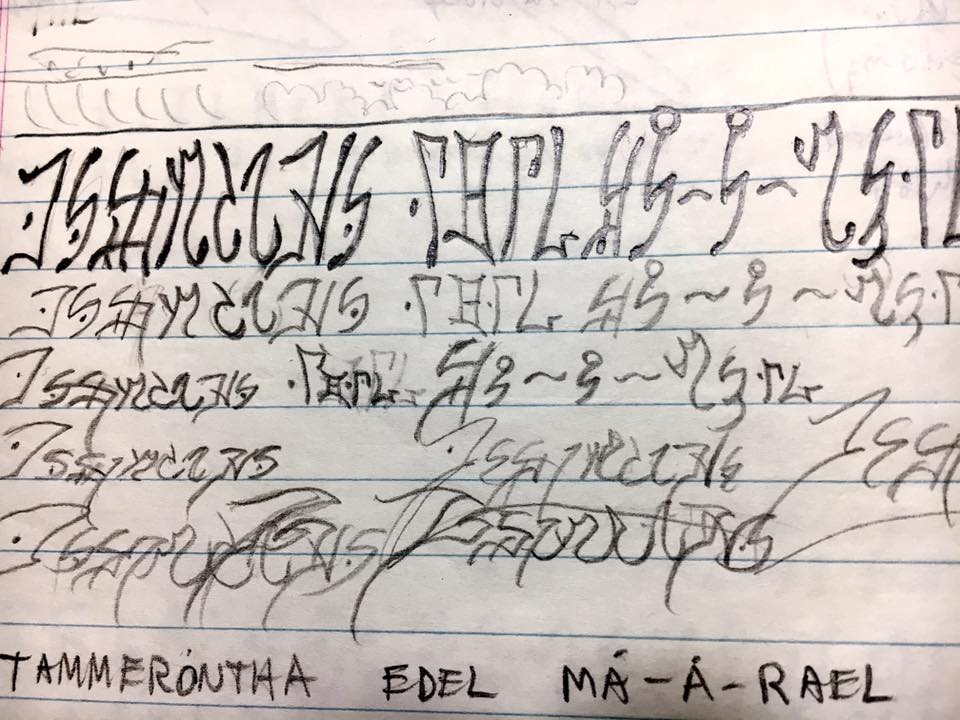

I spent many dark days in the depths of an old 1940’s Texas library pouring through ancient books and old tomes on Gaelic poetry. I then started looking at old Celtic place names in fairy tales and words based on several types of Gaelic and the Cymric Welsh tongues for inspiration. That then inspired me to create what I call my own fairy “roots and stems”, building blocks for my fairy tongue which began to feel more closely connected to the homelands of my books than the Celtic names found in these ancient manuscripts of old Ireland. My languages would be built from these new sounds that felt soft and inviting, something reminiscent of old elvish culture itself, something that seemed to flow naturally as I wove them into the narrative of my stories. Such exotic yet sweetly simple words would become the basis for all my fantasy languages. I then felt the pleasure in such an exercise and the artifice of it all disappeared from my mind.

I started creating my language by picking vowel sounds I liked and choosing popular pronunciations in my place names derived from ancient Irish and Celtic manuscripts. I then added basic consonant sounds, developing very short one or two-part words from these. Building on derivations of these roots and attaching basic meaning or translation to each as I did, I found I was able to quickly construct new compound words and phrases that sounded very original and fresh. These parts could be puzzled-pieced together naturally to form sentences and phrases with even more meaning. I then saw the power of my new fantasy language and what depth it truly had created for me.

I was never interested in linguistics as a means to an end or using languages to buttress Realism in my fiction. My ultimate reason for creating this tongue was purely ornamental. But as I built new words I quickly got sucked into the joy of the exercise and found the sounds of my names and characters very pleasant to the ear. The new words were very simple to construct, unlike Tolkien’s. And yet I felt some kindred spirit to the old Master and how and why he too got sucked into building such a thing.

It seemed to feed itself, like a game, this language building. I saw how one could continue for years doing such an exercise, endlessly learning its nuances and expanding upon them with many new wonders to discover over time.

Some of the characters and place names really are beautiful. They seem to be very elegant names that sound very Celtic, like Breddwyn (breth-win, ‘white wood’) or Avaras (‘land of twilight’) or Avredd (av-reth, ‘Land of the Afterlife’) or Connewe (con-ew, ‘witch hazel’).

I found in creating this fairie tongue that my words in my stories not only sounded authentic but were just easier to pronounce than stuff made up in earlier work. But the real benefit was the hidden meaning behind them created when roots and stems were combined creatively to form larger more complex words. As I mentioned, the true value in these word exercises was the construction of meaning. And so I found my system served that purpose well for me. For the mytho-poetic quality of my work was paramount to me.

In the end I found language construction did not have to be fancy, exhaustive, or comprehensive. In fact, the simpler my fairy tongue was the more elegant it really was in the books in describing characters and place-names. Best of all it felt more approachable than Tolkien’s tongues, and maybe more acceptable by a new reader. In that sense, I would say anyone putting forth the effort to construct languages should not focus on realistic linguistics but fluid, rational, and reusable word-building tools that allow your readers to intuitively sense the deeper meaning behind the artificial words you construct.

In creating any Fairy Tongue in your fiction it is the ‘suspension of disbelief’, not the realism of the language itself, that is important. It is the beauty and the spirit of it that truly matters as it too is an art form unto itself with value. Too many young people get stuck in its construction. Its poetic forms are what matter. For the value of fantasy comes not from its artifice but from its art, in the end.

– the Author

Created Nov 20, 2016, 3:43 AM